In 2025, whispers of a new scramble for Africa ripple across the continent. Western corporations, cloaked in the green rhetoric of sustainability, are poised to claim a tenth of Liberia’s land for carbon credits, a modern echo of the colonial land grabs that once stripped nations bare (X: @CSPGross, April 6, 2025). Meanwhile, in Pakistan, floodwaters from 2022’s catastrophic monsoon still haunt communities, a disaster fueled by a warming planet they did little to heat (FairPlanet, 2024). The air grows heavier each year, thick with carbon, inequity, and the unresolved weight of history. The Global South, long exploited for its resources, now bears the brunt of a climate crisis it did not create, while the Global North negotiates solutions from air-conditioned halls. How did we arrive at this precipice, where the descendants of the colonized are left to drown, burn, or barter their lands for the sins of empire? The answer lies in climate colonialism, a legacy of historical injustices that continues to shape the unbalanced power dynamics of today’s climate policies.

What is Climate Colonialism?

Climate colonialism is no mere metaphor; it is a structural reality where the ecological debts of colonial exploitation compound into modern climate burdens. Scholar Farhana Sultana describes it as the “unbearable heaviness” of a world where racial capitalism and environmental degradation intertwine, disproportionately afflicting the Global South (Sultana, 2022). Historically, European powers plundered timber from India, rubber from the Congo, and sugar from the Caribbean to fuel their industrial ascent, leaving behind degraded ecosystems and dependent economies. Today, this legacy manifests in unequal emissions burdens and policy frameworks that favor the powerful. The Global North, responsible for over 50% of cumulative CO2 emissions since 1850, thrives on resilience built from that plunder, while Africa, home to 17% of humanity, accounts for just 3% (Carbon Brief, 2023). Climate colonialism, then, is the continuation of this imbalance, where historical polluters dictate terms and the exploited are left to adapt or perish.

A History of Extraction, A Future of Vulnerability

The roots of this crisis stretch back to the colonial era. From the 16th century, empires like Britain and France transformed the Global South into a resource frontier, felling forests and mining soils to power the Industrial Revolution. Carbon Brief’s 2023 analysis reveals a striking shift: when colonial emissions are reassigned, say, Britain’s coal burned with India’s resources, the historical responsibility of the North swells further. This was not just economic theft; it was ecological sabotage. Indigenous systems of land stewardship, from agroforestry in the Amazon to water management in the Sahel, were dismantled, leaving regions ill-equipped for future shocks (Whyte, 2023). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Sixth Assessment Report explicitly ties this colonial legacy to today’s climate vulnerability, noting that underdevelopment amplifies the South’s exposure to droughts, floods, and heatwaves (IPCC, 2022).

The numbers tell a stark tale. The United States and Europe, with their centuries of fossil fuel reliance, built wealth and infrastructure to weather a warming world. Meanwhile, small island nations like Vanuatu, contributing less than 0.1% of global emissions, face erasure by rising seas. In sub-Saharan Africa, prolonged droughts cripple agriculture-dependent communities, while South Asia braces for intensifying monsoons, crises magnified by poverty and inadequate systems, both scars of colonial rule (Hickel et al., 2022). As Kyle Whyte argues, this is “colonial déjà vu,” where Indigenous and Southern peoples endure the fallout of a modernity they were never invited to shape (Whyte, 2023).

A History Written in Carbon

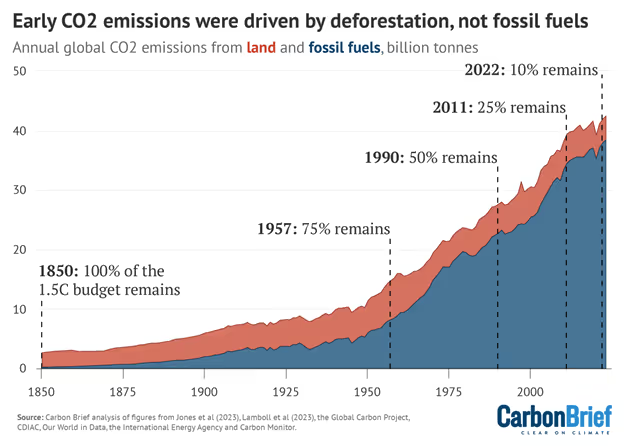

Before fossil fuels became the dominant driver of global emissions, deforestation and land-use change, particularly in colonized regions, were the primary sources of carbon dioxide. In 1850, when industrialization was taking root in Europe and North America, 100% of the carbon budget compatible with 1.5°C of warming remained, as illustrated in Carbon Brief’s graph titled “Early CO₂ emissions were driven by deforestation, not fossil fuels.

Annual global CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and cement (dark blue) as well as from land use, land-use change and forestry (red), 1850-2023, billions of tonnes. Source: Carbon Brief analysis of figures from Jones et al (2023), Lamboll et al (2023), the Global Carbon Project, CDIAC, Our World in Data, the International Energy Agency and Carbon Monitor. Chart by Carbon Brief.

This graph shows that early emissions were largely due to land-use changes (in red), including massive deforestation in colonies to make way for plantations, mining, and infrastructure. Fossil fuel emissions (in blue) only overtook land-based emissions post-1950s, when the Global North accelerated its industrial activities. By 1957, only 75% of the 1.5°C budget remained; by 1990, 50%; and by 2022, a mere 10% remained, bringing the world dangerously close to climate tipping points.

Yet, this historical degradation was largely a function of imperial policies, where natural resources in colonized nations were ruthlessly extracted to fuel wealth in colonial capitals. Forests were felled in India and the Congo, oil was siphoned from the Middle East, and coal powered industries in Britain, while the costs, environmental and human, were externalized to the colonies.

Redrawing the Carbon Map: Colonial Emissions Reconsidered

Carbon Brief’s groundbreaking analysis revealed how colonial rule artificially inflates the Global North’s historical emissions responsibility. The chart below, “Colonial rule boosts European share of historical emissions,” radically reshapes how we assign carbon accountability.

The top 20 countries for cumulative CO2 emissions from fossil fuels, cement, land use, land use change and forestry, 1850-2023, billion tonnes. CO2 emissions that occurred within each country’s national borders are shown in dark blue, while those that took place overseas during periods of imperial rule are coloured red. Emissions reallocated to former imperial powers are shaded light blue. EU+UK is shown in addition to the relevant individual countries. Source: Carbon Brief analysis of figures from Jones et al (2023), Lamboll et al (2023), the Global Carbon Project, CDIAC, Our World in Data, the International Energy Agency and Carbon Monitor. Chart by Carbon Brief.

When emissions from controlled territories are added to colonial powers, the historical carbon footprints of European nations increase dramatically. For instance:

- The UK’s cumulative emissions rise significantly when factoring in emissions from the British Empire.

- The EU+UK bloc, when adjusted for colonial control, nearly matches or exceeds the US in cumulative historical emissions.

- India and Indonesia’s emissions drop when their colonial-era carbon is rightly attributed to Britain and the Netherlands, respectively.

These recalibrations are not just statistical adjustments but they are moral correctives. They reveal that nations like the UK, France, and the Netherlands benefited from carbon-heavy industrial growth financed by colonial exploitation, while the countries they ruled now suffer disproportionately from climate change.

Modern Policies, Old Power Plays

Today’s climate policies, intended to mend this fractured planet, often deepen these wounds. The Paris Agreement promises global cooperation, but its tools: carbon markets, climate finance, and technology transfers mirror colonial hierarchies. In 2009, rich nations pledged $100 billion annually by 2020 to aid poorer countries, yet by 2025, this remains a broken promise. Much of what trickles through arrives as loans, not grants, shackling debt-ridden nations further— a sleight-of-hand reminiscent of imperial benevolence (Global Justice Now, 2023). X users like @BoutierIndira (April 9, 2025) decry this as “top-down colonial nonsense,” pointing to India and the DRC as examples of sidelined voices in a Northern-led agenda.

Carbon markets, hailed as innovative, often serve as a new frontier for exploitation. Under schemes like the Clean Development Mechanism, Northern firms offset emissions by funding projects in the South projects that can displace communities or seize land for profit. In Cambodia, brick kilns tied to Western supply chains churn out emissions while locals bear the health costs, a pattern Laurie Parsons dubs “carbon colonialism” (Parsons, 2024). Similarly, reforestation efforts in Africa, as @CSPGross notes, threaten sovereignty under the guise of green salvation. Peter Newell warns that such mechanisms let polluters delay decarbonization at home, outsourcing the burden to those least equipped to resist (Newell, 2023).

Silenced Voices, Stifled Solutions

The marginalization extends to the negotiating table. At climate summits, Global South delegates, hampered by visa issues, funding shortages, or language barriers, struggle to pierce the polished rhetoric of Northern counterparts. Their calls for loss-and-damage funding, a fair carbon budget, or technology access are deferred or diluted (Sultana & Loftus, 2024). This echoes the colonial silencing of local knowledge, a grievance echoed on X by @b_kesselman (April 10, 2025), who asks why African Indigenous practices aren’t prioritized over Western tech fixes.

Yet, the South holds vital answers. Indigenous agroforestry in Brazil or traditional water harvesting in India offer resilience honed over centuries solutions dismissed in favor of Northern patents like carbon capture (Whyte, 2023). The Lancet Planetary Health warns that mainstream mitigation models perpetuate this inequity, preserving Northern lifestyles while offloading costs southward (Hickel et al., 2022). The result is a climate agenda that prioritizes the powerful, leaving millions to face floods like Pakistan’s in 2022, without adequate support (FairPlanet, 2024).

Toward a Decolonial Climate Future

Breaking this cycle demands more than platitudes; it requires reckoning with history. Climate colonialism is not fate but a manufactured inequity, sculpted by centuries of greed and neglect (Greenpeace UK, 2022). To dismantle it, we must deliver on climate finance, grants, not loans with no strings attached, as Global Justice Now (2023) urges. We must amplify Southern voices, ensuring they shape policies rather than merely endure them, a sentiment X users champion fiercely. And we must center local solutions, Indigenous and community-led over imported techno-fixes, as Confronting Climate Coloniality advocates (Sultana & Loftus, 2024).

Material accountability is key. Historical polluters owe a climate debt, reparations through debt cancellation, technology sharing, or direct funding for adaptation and loss-and-damage, as demanded at COP28 and beyond. The Conversation’s Harriet Mercer notes that even leading scientists now link colonialism to climate change, a shift that must translate into action (Mercer, 2022). For the millions in the Global South watching their lands dry, their homes flooded, and their futures slip away, this is not optional, it is survival.

A Call to Reimagine Justice

The climate crisis is no blank slate; it is a canvas streaked with the brushstrokes of empire. To ignore this is to settle for half-measures that sustain the powerful while the vulnerable pay. Can climate justice exist without dismantling these colonial legacies? For the sake of Pakistan’s flood survivors, Liberia’s threatened forests, and countless others, the answer must be no. The time for reckoning is now, let us confront the ghosts of climate colonialism and forge a future where equity, not exploitation, defines our path.

References

- Carbon Brief (2023). "Revealed: How Colonial Rule Radically Shifts Historical Responsibility for Climate Change." https://www.carbonbrief.org/revealed-how-colonial-rule-radically-shifts-historical-responsibility-for-climate-change/

- FairPlanet (2024). "How Climate Colonialism Affects the Global South." https://www.fairplanet.org/story/how-climate-colonialism-affects-the-global-south/

- Global Justice Now (2023). "Colonialism, Climate Change and Climate Reparations." https://www.globaljustice.org.uk/blog/2023/08/colonialism-climate-change-and-climate-reparations/

- Greenpeace UK (2022). "Confronting injustice: racism and the environmental emergency" https://www.greenpeace.org.uk/challenges/environmental-justice/race-environmental-emergency-report/

- Hickel, J., et al. (2022). "Existing Climate Mitigation Scenarios Perpetuate Colonial Inequalities." The Lancet Planetary Health. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(22)00092-4/fulltext

- IPCC (2022). "Sixth Assessment Report: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability." https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/

- Mercer, H. (2022). "Colonialism: Why Leading Climate Scientists Have Finally Acknowledged Its Link with Climate Change." The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/colonialism-why-leading-climate-scientists-have-finally-acknowledged-its-link-with-climate-change-181642

- Newell, P. (2023). "More than a Metaphor: ‘Climate Colonialism’ in Perspective." Global Social Challenges Journal. https://bristoluniversitypressdigital.com/view/journals/gscj/2/2/article-p179.xml

- Parsons, L. (2024). Carbon Colonialism: How Rich Countries Export Climate Breakdown. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Carbon-Colonialism-How-Rich-Countries-Export-Climate-Breakdown/Parsons/p/book/9781032533667

- Sultana, F. (2022). "The Unbearable Heaviness of Climate Coloniality." Political Geography. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2022.102638

- Sultana, F., & Loftus, A. (Eds.). (2024). Confronting Climate Coloniality: Decolonizing Pathways for Climate Justice. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Confronting-Climate-Coloniality-Decolonizing-Pathways-for-Climate-Justice/Sultana-Loftus/p/book/9781032737850

- Whyte, K. (2023). "Is it Colonial Déjà Vu? Indigenous Peoples and Climate Injustice." Humanities for the Environment. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2925277

About the author

Nelson Izah is a dynamic youth leadership professional and social impact advocate, pursuing a Geology and Mineral Exploration degree at Kazakh British Technical University. As National Country Coordinator for the Hult Prize in Kazakhstan, he drives entrepreneurial initiatives across universities. With five years of cross-sector leadership experience, Nelson has mobilized youth programs through Voluntary Service Overseas (VSO), STEMi Makers Africa, and the Autism Awareness Foundation. Through DoTheDream Youth Development Initiative, he has empowered over 3,000 students in Lagos state. Currently, he volunteers as a writer for Re-Earth Initiative, focusing on policy and education.

.avif)